Behind the Lines

The work of Missouri’s Child Abuse and Neglect Hotline Unit

Introduction

Much has been written and shared about child abuse and neglect cases (CA/N). For most of those featured in the media, you’re hearing about extreme cases of physical, emotional or sexual abuse in which the choice to remove the child from the situation is an obvious one. But for many cases, a hotline call is what begins a process of difficult decisions about whether to investigate and determine if that child should be removed from their home. Very little is written about this first step and the people behind the difficult work of protecting children, the state staff who work behind the phone lines at the Department of Social Services (DSS), Children’s Division (CD) Child Abuse and Neglect Hotline Unit (CANHU), in the battle against child abuse and neglect in Missouri.

This article will tell you about these devoted, skilled workers who do a job many say they could not do, even if it meant saving children. You’ll get a glimpse into the world of the child abuse and neglect hotline unit (CANHU) for Missouri – the difficulties of staffing and managing secondary trauma, and the volume and type of calls. We’ll also look at the history of the work of the hotline and how it has progressed through the years, including adapting to changes in social norms, changing state laws and technology developments.

By taking you inside the 24/7 call center for child abuse and neglect in Missouri, you will have a better understanding of the seemingly never-ending trauma happening to children every day because of things like drugs, poverty and mental illness. You will share in the work of everyday heroes behind the scenes.

This article will not focus on what happens after the determination is made to send the report to a DSS CD investigative field worker. No judgement is made on any policies, laws or individual decisions by DSS that impact child welfare. We will not be comparing Missouri’s hotline to other states’ hotline systems. Each state approaches child abuse and neglect somewhat differently. Every state has their own state laws governing this work. Our purpose for this article is to give you, the reader, a better understanding of the uniqueness and complexity of this work.

Staffing and Training

The Child Abuse and Neglect Hotline is operated by the Department of Social Service (DSS) Children’s Division (CD). Hotline workers are required to have the same qualifications as Children’s Division field investigators, holding at least a bachelor’s degree in social work or a related field, and they receive the same benefits and career development opportunities.

Currently, the unit is staffed with 50 Children’s Service Workers (part-time and full-time) with 7 Children’s Service Supervisors, a Children’s Service Specialist, a Trainer dedicated to CANHU staff, and a Unit Manager. All staff are scheduled to provide maximum 24/7 coverage based on call data. Work schedules overlap to provide continuity with part-time workers filling coverage gaps as needed. During the period of highest call volume (Monday – Friday mid-afternoon), there are as many as 24 workers taking calls with 3-4 supervisors on duty. Supervisors are scheduled seven days a week on all shifts except for midnight shift when they are available on call. Supervisors are actively involved in call consultation throughout the work day and are readily available to assist with difficult calls.

The average tenure is 5 years, but there are some workers who have been with the hotline for as long as 22 years. For supervisor and management positions, the average tenure is 18 years. Given the nature of the work, turnover is an ongoing challenge. Historically, some of the turnover is due to workers moving between the hotline and the field. Many workers come in with a desire to end up in the field working directly with families. These workers are uniquely skilled because they are the ambassadors and educators for the work done ‘on the other side’.

Because of a targeted increase in funding from the Missouri Legislature, in 2014 Children’s Division built a career ladder for workers, including those at the hotline. Before the career ladder was in place, the only promotion was to become a supervisor. Career ladder hotline staffers who don’t want to supervise but want to continue taking calls, can be promoted by developing expertise in a particular area and becoming specialists and coaches to other workers by modeling best practices. This serves to keep the best people behind the lines.

CANHU workers start out with 3 weeks of training before they begin to take calls on their own. They spend the first two weeks working through scenarios and policies, and during the last week of training they answer calls with the trainer. Workers receive ongoing support including peer-to-peer coaching through call record reviews. All workers are offered annual professional development. The focus on continuous support serves to reduce high turnover.

Unlike some states where call information is simply recorded and shared with investigators or sent to a next level screening team, hotline workers in Missouri are tasked with determining, during the call, whether CD has authority to intervene with the family and if so, what type of intervention and how quickly. Placing this decision with the hotline staff reduces the amount of time for a child to be seen and safety to be addressed by field staff.

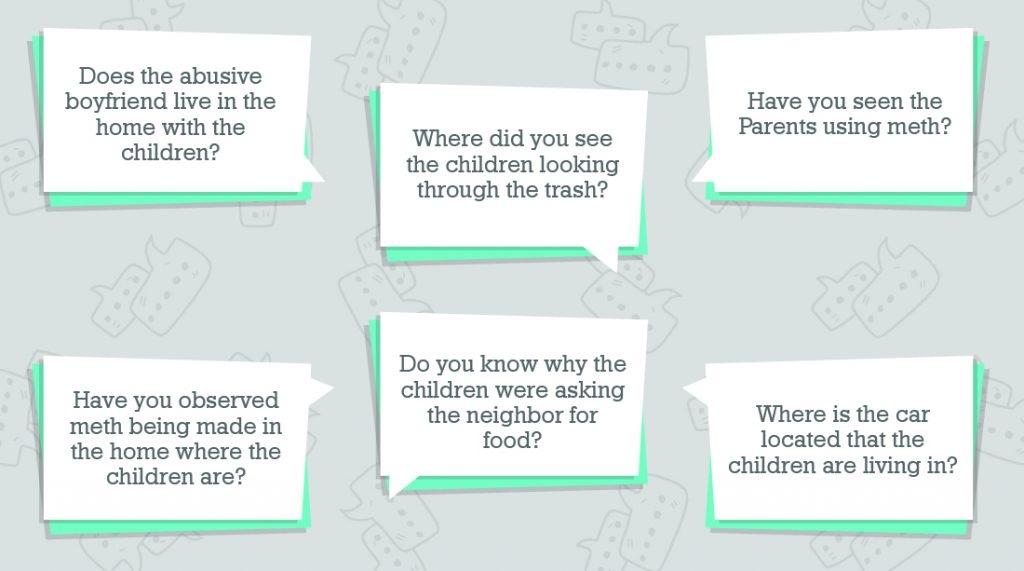

The information the caller gives leads the hotline worker to choose among 30 ‘pathways of concern’. The pathways of concern were developed to reflect the most frequent types of caller concerns over the hotline’s history – the most common triggers for child abuse and neglect. Callers can allege more than one concern and each pathway has a series of standard questions that guide the interview. (Note that not all pathways are child abuse or neglect.)

Protocols for the calls

Missouri Department of Social Services, Children’s Division Child Abuse and Neglect Hotline Unit staff are highly skilled workers who follow a structured process that has been developed over the course of the hotline’s history and codified in state law. The hotline staff use the well-established, evidence-based structured decision-making (SDM) approach to child protective services. SDM gives the workers clearly defined decision-making criteria to assess the risk and determine response priority. Hotline workers are responsible for categorizing the call, and determining how soon the child needs to be seen – within three (3), twenty-four (24) or seventy-two (72) hours.

The system of how calls are taken and addressed is complex and includes many terms of art that are commonplace in the hotline’s lexicon. What follows are the most common terms used by the hotline for decision-making and what they mean.

“Screened In” Calls are calls sent to the field for appropriate follow up and further assessment of the child’s safety. They are sent to the field office coded as a CA/N Investigation, a Family Assessment or a Non-CA/N Referral.

A CA/N report (when the caller reports child abuse and neglect allegations) must meet the statutory definition. These reports result in either a field investigation or family assessment. By law, the child must be under the age of 18 at the time of the call, meet the legal definition of abuse or neglect and the alleged perpetrator must have care, custody, and control of the child. CA/N reports are typically assigned to the county where the child resides. An investigation is the collection of physical and verbal evidence to determine if a child has been abused or neglected. State law requires CD to ask law enforcement to co-investigate in these situations.

A Family Assessment is the process CD field staff use to assess and verify the child’s safety and the family’s need for services, with the goal of reducing any future risk of abuse or neglect. CD may address allegations of child abuse or neglect that would not lead to criminal charges, through the family assessment process. If at any time during the assessment the child’s safety cannot be assured, the CD field staff may conduct a CA/N investigation.

A Non-CA/N referral results from a call that does not meet the statutory definition of child abuse and neglect. The hotline codes these calls as non-CA/N referrals so that the field staff responds to the call with appropriate intervention for the child, provision of services to the family or referral to other community resources. Non-CA/N referrals are used for a variety of calls where an intervention is needed:

- A preventative service referral is a call of concern about a child in CD custody, a child who is receiving CD services, or a child who may need placement (or an intervention to resolve the need for placement) when no CA/N is alleged.

- A newborn crisis assessment is when a medical provider calls reporting a newborn who tested positive for drugs or has signs of alcohol exposure, or the mother has a positive drug test at birth or has signs and symptoms of alcohol misuse.

- A non-caretaker referral is a call in which alleged physical or sexual abuse has happened to a child by another child or adult who does not have care, custody, or control of the child. By recent state law CD responds with a family assessment to calls alleging sexual behavior by children under the age of 14 with another child.

- Non-CA/N fatality is a determination that can be made when a medical examiner and coroner calls the hotline to report a fatality of a child under the age of 18. Depending on the information from the reporter, the hotline takes the report as a non-CA/N fatality, which means that the death was caused by other than CA/N. The hotline always does a prior CA/N history check for the medical examiner or coroner.

“Screened Out” calls (approximately 22% of calls), also called documented calls, occur when the allegations do not meet the requirements of a CA/N report or a non-CA/N referral, there is insufficient information, or the child cannot be found for follow up in Missouri. These calls are not sent to CD staff, but are documented in the system and retained for one year, to serve as background documentation in case further calls come in on the same child. If three documented calls are received within 72 hours on the same child, the calls will be reviewed together to see if the information collectively is enough to meet the state statute, or alternatively to see if the family, parent or caregiver is being harassed.

A day in the life of a worker

At first glance, the room and everything in it, looks like the typical call center. Lots of high- walled cubicles, workers settled into their chairs comfortably prepared for hours of sitting, head-sets in place, and two monitors open and ready for typing. They do not appear to be distracted by the clock or their personal devices. Instead they’re consumed by the intense subject matter that can be heard floating through the air in the form of conversation bits about violence, drugs, physical abuse, sexual abuse, extreme neglect and danger. The questions and statements are calculated and specific, with one goal, determining what is happening to the child(ren).

Hotline workers come in each day well-prepared to hear things most of us would never want to hear. They log into their system, check their email and jump right on a phone call, one of many throughout the day. The system sends calls to each worker in a systematic way, based on algorithms, to ensure that calls are assigned and distributed quickly and equitably. Each worker can see the number of calls in their queue, the number of calls waiting, the staff who are currently on calls and the longest wait time for callers in queue. The queue is ever-present, but the workers remain focused on their intake role, efficiently gathering the most accurate details they can. They focus on the child(ren) at hand, but work to keep the call moving forward in a structured way, always mindful that the next call could be life or death for a child. During any given day, these workers can be expected to answer up to 21 calls, or an average of three calls an hour during an eight-hour shift.

Workers communicate with each other over email during the day, rarely leaving their cubical except for meal and restroom breaks. Supervisors are always available to advise on any calls throughout the shifts of a 24 hour day. Each cubical appears to have some small personal touch that serves as a reminder when a worker feels the weight of the words they’re hearing.

Because of the structured questions format, and the variety of pathways that can be identified through the caller, calls take as long as staff feel is needed to provide as complete a picture as possible of the family structure and relationships. Workers compile contact information and as many details as they can about the alleged abuse or neglect. Despite the structured questions and pathways, the calls are conversational, guided, reassuring, gently moved along. Sometimes key information may be lacking, for instance a caller may not personally know the child(ren) or alleged perpetrator whom they’re calling about, so they have no name to give. They may not be able to provide a known address, just a description. The worker persists, asking questions while at the same time searching their data systems for confirmation of critical information. They want to give the investigative field staff as much information as they can in order to help them start the investigation or family assessment. They always check to see if there are prior CA/Ns in the system. Callers are always asked whether they are aware of guns, vicious dogs or other things that would put the field investigator in danger when they go to the location.

When a family cannot be located by regular means – address, school, etc. they do an exhaustive search of accessible data, even social media. These workers will not allow a potential tragedy for a child because they did not look at all the information they have access to. They know that field staff don’t have time to do this kind of search, given that some children have to be located in as little as 3 hours.

The hotline staff is meticulous about completing the structured decision questions. These protocols offer consistency designed to direct the call despite the challenges of the information gathering. This can be difficult because of complexities such as numerous child victims, non-traditional family structures, multiple and varied allegations, long winding narratives, callers who are angry, calls meant to harass someone, or calls that are not made in good faith. Workers will spend a brief time after the call completing the details, but they will in almost all cases, end the call with a decision about how to proceed.1

This means the hotline worker has an important decision to make – whether to ‘screen in‘ the call, categorize it as a Child Abuse/Neglect investigation or Family Assessment, and determine how soon the child needs to be seen by the CD field investigators. Hotline staff understand that the decisions they make ‘follow’ the family, and that a balancing act of family privacy and autonomy with child protection often means that they ‘never get it right’ in someone’s eyes. Many of the calls come in to the hotline simply because there is nowhere else to go to be heard, particularly during the night and holidays.

The best way for readers to understand the complexity, volume, variety, and trauma of the calls that workers take is to share fictionalized calls based on real calls. This is a sampling of the calls a worker may receive in a single day. On average a call lasts between 15-20 minutes.

Definitions of permissive and mandated reporters:

Mandated reporters: Individuals required by state law to report child maltreatment. (see RSMo 210.115.1). These are members of designated professions, and those who typically work around or have frequent contact with children. Missouri law designates the following:

- Health care professionals (physicians, medical examiners, coroners, dentists, chiropractors, optometrists, podiatrists, residents, interns, nurses, hospital or clinic personnel or other health care practitioners);

- Psychologists and other mental health professionals;

- Social workers;

- Child-care (day care) workers;

- Law enforcement officials (police officers, juvenile officers, probation/parole officers, jail or detention center personnel);

- Teachers, principals, and other school officials;

- Ministers; and

- Other persons with responsibility for the care of children

Permissive Reporters: Those who are not required by law, but report voluntarily are referred to as permissive reporters.

Secondary Trauma

Secondary trauma changes one’s world view. Hotline workers are exposed daily to information that many people may never hear or know. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network defines Secondary Traumatic stress as “the emotional duress that results when an individual hears about the firsthand trauma experiences of another. Its symptoms mimic those of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), often seen in soldiers who’ve spent time in combat. People affected by secondary stress may find themselves re-experiencing personal trauma or notice physical reaction to the indirect trauma exposure. They may experience changes in memory and perception; or they may develop trust issues. Hotline workers are at-risk for secondary trauma simply because of the calls they take, trauma is at the heart of most of the calls. Beyond the obvious cause of the trauma, there are other factors and experiences contributing to the trauma experience. Some of the distinct factors include:

- Calls are recorded, workers can feel as if everything they do is scrutinized and monitored.

- All child deaths in the state of Missouri are required to be reported to CANHU.

- Currently, CANHU workers are not authorized to see what happens with the child(ren)after the call ends.

- Sometimes callers will tell workers it is their fault if they don’t take the call as a CA/N report and something happens to the child.

- They must use critical thinking skills all day, and making the wrong decision could be fatal for a child.

To mitigate trauma, the hotline provides intensive training and supervision during the first year, which is often the hardest. During the training, staff spend time discussing work-life balance, and hobbies outside of work to help combat trauma. The supervisor will listen in on calls for the first few months. A supervisor will debrief calls with the worker during and after each call for the first six months to a year. After the first year peer report evaluations are completed and supervisors give feedback based on reviews and rating from experienced workers.

How Changes in Policy and Law have influenced the Hotline

This section will describe some of the legislative and policy decisions that have changed the hotline over time. The Missouri Child Abuse and Neglect Hotline Unit has been in place since 1975. Missouri was one of the first states to have a centralized unit. In August 2004, the most transformative legislation passed requiring the Children’s Division to develop and use structured decision-making protocols for all child abuse and neglect reports. Automation followed using decision-making logic to improve the consistency and accuracy of the work, while allowing flexibility to follow the caller’s narrative. 2004 was a tipping point for the hotline, moving it from functioning like a help center “What can I help you with” to an official call center “Are you calling to make a report of child abuse or neglect?”

A few pieces of critical legislation passed in the 1990’s are worth noting as they were key in influencing the hotline’s development. RSMo 58.452 requires coroners and medical examiners to report all child deaths, under age 18, to the Children’s Division. Today, CANHU workers take these calls, some of which result in Child Fatality Reviews by law, others are coded as non-CA/N. While child death calls are a small percentage of calls received, they are among the most traumatic for staff.

RSMo 191.737 requires health care providers to report children who, at birth, have been exposed to a controlled substance or alcohol. While state law directed these reports to Department of Health and Senior Services, the CA/N hotline has taken those calls since 1991.

In 2013, another major change came about through legislation, affecting mandated reporters, those who are required by state law because of their occupation to report abuse or neglect when they have reasonable cause to suspect. In the past, mandated reporters who worked together in the same work setting could choose to make a single report rather than each observer making a call to the hotline. The law, RSMo 210.115.1 now requires each mandated reporter to report, unless they are members of a medical institution. (A single report is allowed from a designated member of a medical team.) This legislation had an immediate and significant impact on CA/N reports as a proportion of calls that required a field investigation or family assessment. CA/N reports increased that state fiscal year by 7,000.

In 2015, legislation passed, RSMo 210.148 requiring CD to respond with a family assessment approach to children and families in which the subject of a hotline call is a juvenile under 14 who is alleged by the caller to be sexually acting out with another child. This requirement has resulted in increased calls to the hotline.

Also, in 2015, legislation mandating that instructions for calling the child abuse and neglect hotline be posted in all schools, Pre-K through 12, in English and Spanish in public areas and in restrooms, RSMo 160.975. There is a separate toll-free number for these calls designed to make it easy for children to remember. Because these callers may be children, the hotline worked with a child forensic interviewer expert to develop new protocols for interviewing child reporters.

In November 2016, the hotline began offering online reporting for non-emergency calls from mandated reporters. This is one of the interventions to address busy signals and long wait times and to continue the hotline’s efforts to improve efficiency through technology solutions. See Continued Improvement Section for more information about this option for mandated reporters.

Most recently, during the 2017 legislative session, Senate Bill 160 passed, which modified the definition of care, custody and control, RSMo 210.110 and added human trafficking language to definitions of child abuse and neglect. Adults who previously did not fit the definition of caretaker, who are engaged in trafficking or sex trafficking, can now be found to be perpetrators of child abuse and neglect. CANHU anticipates that this will result in more CA/N determinations.

Along with legislative changes, CANHU advances the cause of child safety through its own internal analyses. One of the most complicated issues is parent or caregiver drug use. Drugs are one of the top 5 pathways described in calls to the hotline. The proliferation of opioid misuse and the ongoing crisis with methamphetamine, dual epidemics, are causing an increase in calls to hotlines around the country. Missouri is one of 19 states that has specific reporting procedures for infants who show evidence at birth of having been exposed to drugs or alcohol. Missouri law requires these calls from providers to be immediate referrals. (RSMo 191.737) 2

Before the latest drug crisis, if there was a parental or caretaker drug concern but it did not meet CA/N guidelines it was categorized as a documented call. Now, if the child who is the subject of the call is age 5 or under, the call will be classified as a family assessment if the caller is law enforcement. The drug pathway explores a lengthy series of questions that better evoke from the caller the risks to the child.

Drug use by the parent or caregiver often goes hand in hand with reportable incidents including isolation for the child, not attending school regularly, inability to care for the child by the caregiver, poor hygiene, food and housing insecurity, unsafe shelter, lack of supervision, an overall accumulation of neglect. The Children’s Division is constantly watching trends and engaged in conversations about when calls to the hotline about parent or caregiver drug use constitutes child abuse or neglect.

Continued improvement of the hotline

The Missouri CA/N Hotline is committed to being one of the best in the nation. They are continually improving their practices through recommendations from frontline workers, innovative ideas from hotline staff, supervisor’s input, community stakeholder suggestions, and policy changes.

Online Reporting

Missouri increased hotline access by opening an online reporting site for mandated reporters who are making a non-emergency report (not in imminent danger as determined by the mandated reporter). Reporters are prompted to answer a series of questions designed to determine if the report should be considered an emergency and thus require a phone call. Online reports can be handled in half the time as a phone call by CANHU staff.

From November 22, 2016, when online reporting started, through August 31, 2017, 9,590 non-emergency reports were taken online. The expectation is that this option continues to gain acceptance by mandated reporters, resulting in a more efficient call system for the more urgent cases. Off lining these non-emergency reports reduces the wait time for all callers, and is a more efficient reporting system for mandated reporters. These electronic reports are given the same expertise and focus by the CANHU staff as a call. DSS is working to double the use of the online reporting by the end of this year. Learn more about online reporting.

Expanding hotline staff locations

In August, 2016 the hotline developed its first out-based unit (formerly all hotline workers were located in Jefferson City) to increase capacity and offer the opportunity for individuals to do hotline work in other locations, including field staff. Out-based staff took 6,340 calls from January through August routed to them.

Trauma-informed

The hotline is following the lead of the Children’s Division by working to become trauma informed. Last year hotline staff went through a National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) Trauma Toolkit training by one of the state’s foremost experts on trauma and trauma informed practice, Dr. Patsy Carter. New approaches to processes and communications resulted, including softer messaging for callers to the hotline. “Thank you for calling the Missouri Child Abuse and Neglect Hotline and for being part of Missouri’s Child Protection Network” and to replace busy signals, callers receive the following message “The Missouri Child Abuse and Neglect hotline is currently experiencing a high volume of calls and is unable to take your call at this time. For an emergency or life-threatening situation, call 9-1-1 now and then call the Hotline. Your call is very important to us and to the child you are concerned about; please hang up and try your call again. Mandated reporters can now submit non-emergency reports online: Go to dss.mo.gov and click on the Report Child Abuse& Neglect button. Goodbye.”

CANHU management continues to look for ways to improve agency protocols, break schedules, physical space, policy language, and debriefing procedures to identify and reduce secondary trauma. Children’s Division Central Office Trauma Committee meets monthly to discuss trauma practices throughout the agency, including at the hotline. The goal is for trauma awareness to become embedded in the culture of the hotline, creating a safer, more welcoming environment for workers and callers.

Technology improvements and challenges

Currently the hotline relies, for the most part, on what is often called the ‘plain old telephone system’- the system of copper wires, telephone poles, and analog signals powered by telephone companies. Most of state government has converted to digital phones and infrastructure following the lead of public and private sector industries. Digital phone systems offer flexibility, efficiency and value. What they do not offer yet in the way that the ‘plain old phone system’ offers is the measure of reliability and 24 x 7 support critically necessary to the work of the CANHU.

Changes have been made to how callers with out of state area codes can access the hotline. State law authorizes the CANHU to only handle calls for children within Missouri’s boundaries. Before cell phones, calls from out of state were managed through a separate number. Cell phone technology allows people who become residents of Missouri to keep a phone number with another state’s area code. This meant that the hotline could no longer assume out of state numbers were non-Missouri residents calling to report concerns about children in other states. Because of efforts by Missouri’s First Lady in collaboration with DSS, everyone uses the same toll-free number to reach the hotline, including callers with out of state area codes.

DSS recently brought in a consultant to research, report and recommend the latest industry standards and enhancements for child abuse hotlines.

Disarming the myths

Because of the privacy and sensitivity of this work, there are misconceptions about the hotline. We offer responses to some of the common misconceptions:

Conclusion

The often referenced "Story of the River" seems like a good metaphor for the work of the CANHU staff.

Imagine you and some friends are strolling along the shoreline of a river taking in some fresh air, when you suddenly see a baby floating downstream in the water. You jump in to save the baby. As soon as you get the baby to safety on shore, you notice another baby in the river, with more babies behind that one. Your friends begin assisting you in the water pulling baby after baby out to safety. No one knows where the babies are coming from or how they’ve gotten in the river. Eventually one of your friends suggests that you go upstream to find out where the babies are coming from and stop it. But it’s taking every hand to pull the babies out of the river. What would you do? You know that the work of staying downstream and pulling the babies out of the river is invaluable, but upstream something is causing the babies to end up in the river in the first place. If you can stop whatever that is, you will prevent the babies from this fate.

We do not intend to make them heroes any more than they are in their everyday life. CANHU staff are earnestly, persistently doing the downstream work identifying and getting help for the babies in the river. Twenty-four hours a day, every day including holidays and weekends, well-trained state employees at the CANHU do their part to protect children.

But who is doing the upstream work of keeping children from being tossed into the river? Government cannot alone protect all children.3 Children become collateral damage of poverty, low wages, social isolation, addiction, untreated mental illness, lack of parenting skills. Children live in families, in communities. What are communities willing to do to protect children and strengthen families?

Children need strong capable parents. We need to find ways to help parents upstream before children end up in the ‘river’ of child abuse and neglect.

Want more information?

Some suggested resources:

- The Missouri Children’s Trust Fund is working with families through a strengths-based approach to reduce the risk of child abuse and neglect. The Strong Parents Stable Children materials are available on the CTF website.

- Available Missouri Child Abuse and Neglect Annual Reports

- More info on trauma informed & secondary trauma

- Information on child welfare across the nation

- What other states are doing

- Some commonly asked questions

- Other DSS & CD programs

Endnote- investigative field staff can always change the status recorded by the CANHU staff, after they do their work in the field. CANHU data, which is what is used in this article, is hotline call production data. This data may not reflect the final outcome. All data unless noted is calendar year. Some data may reflect state fiscal year – July through June.

To reach the Missouri Child Abuse and Neglect Hotline, call:

- 1-800-392-3738

- If you’re a student, call 1-844-CAN-TELL

- TDD: 1-800-669-8689

To reach the School violence hotline, call:

- 1-866-748-7047

- Online: https://www.schoolviolencehotline.com/

- Download: the free “MO ReportIt” App from your App store

- Text: “ReportIt” to 847411. Include school name and city.

Missouri KIDS COUNT wants to express our deep gratitude and respect for the staff, supervisors and manager of the Child Abuse and Neglect Hotline. Until now, Missouri Kids Count, and, we expect many of you reading this had no idea what happens every day, non-stop, in this special place in state government solely devoted to protecting children. The CANHU staff did not ask for our recognition, nor do they allow attention like this article or media attention to interfere with their single-minded work. They did graciously work with us and allow us to observe their work so that we could tell their story and do our part to focus attention on Missouri’s at-risk children (particular thanks to Charlotte, Casey, Chelle and Camille).

Suggested Citation

Hines, L., Schaumburg, K., Gooch, C (2017 September). Behind the Lines: The work of the Missouri Child Abuse and Neglect Hotline. The Family and Community Trust (FACT) – Missouri KIDS COUNT. Available at: http://mokidscount.org/

Footnotes

1 The worker will notify the caller of the call decision and the phone number for the assigned field office for identified reporters.

2 Missouri, along with 19 other states, has a criminal statute wherein the manufacture or possession of methamphetamine in the presence of a child is a felony, and exposing children to the manufacture, distribution or possession of meth is child endangerment. (RSMo 568.045).

3 There are over 1.3 million children under 18 in Missouri.

Download Behind the Lines Article

October 18, 2017