School Nurses and School-based Healthcare: The Data and the Stories

“The misconception that school nurses are not ‘real’ nurses continues to prevail because many aspects of school nursing remain unknown…people don’t know what we actually do.” — Dana Fifer, District School Nurse Manager at North Kansas City School District

In the first article of this series, we presented information about the history of school nursing along with a brief description of the roles and responsibilities of school nurses in Missouri (the first article in this series can be accessed here).

This article details the array of conditions that school nurses encounter in Missouri’s public schools. In the first section, we present the latest data reported by school nurses using the Inventory of Students with Special Health Care Needs, along with trends for selected conditions over the last decade. In the second section of this article, we share inspiring leadership stories from school nurses around Missouri and their efforts to address child health needs through community engagement.

While reading this article, we invite you to notice the chronicity of the conditions that school nurses address in the school setting. Where many nurses work in settings such as hospitals, clinics, or nursing homes, and among colleagues providing peer support and consultation, the school nurse is often the only health professional in the school setting. School nurses represent a unique nursing discipline which requires care and support for a wide range of children with medically complex and chronic diseases to fully healthy children—all set in a non-healthcare environment.

Missouri Health Inventory

For the past 10 years, school nurses in Missouri have collected information on the health needs of students attending public schools using the Inventory of Students with Special Health Care Needs. Missouri is one of only 5 states that have collected this kind of child health data consistently over this extended period of time.

- The primary purpose of the Inventory of Students with Special Health Care Needs is to help identify trends in health conditions and health needs of children so that the State School Nurse Consultant can provide relevant professional development opportunities and tools for school nurses.

- The inventory has been completed voluntarily every other year by the Lead School Nurse in each public school district. Starting the 2015-2016 school year, the inventory will be completed annually.

- To protect the confidentiality of all students, the Lead School Nurses only report to the state unnamed data (no names or identifying information is included).

- The Lead School Nurses collect student diagnostic information from health records provided by caregivers.

- The State School Nurse Consultant, with the Department of Health and Senior Services, collects the data from each Lead School Nurse and develops an overall summary at the state level.

- Students identified with multiple conditions are counted in each of the conditions reported.

- Responses to the inventory represent approximately 90% of the students enrolled in public schools in a given year.

- In Missouri, nurses’ response rates to the inventory have been high thanks to the long standing and trusted relationship between the State School Nurse Consultant and the School Nurses.

School Health Data Efforts at the National Level

The National Association of School Nurses and the National Association of State School Nurse Consultants began in 2014 to develop a national, uniform, standardized database for all school nurses. This national database includes information on health services, staffing in schools, disposition of students seen in the health office, and students diagnosed with any of five chronic health conditions: asthma, life-threatening allergies, seizure disorders, and diabetes type I and II. The database does not include information on everything a school nurse does, but it provides the minimum information needed to show the effects of school nursing on a student’s health and education. It is anticipated that the current database may expand in the future as more is learned about the interaction between health and education.

In the following section, we present an overall summary of the school health data collected by school nurses in Missouri for the 2014-2015 school year—the most recent data available. The 2015-2016 school year data is currently being collected and analyzed.

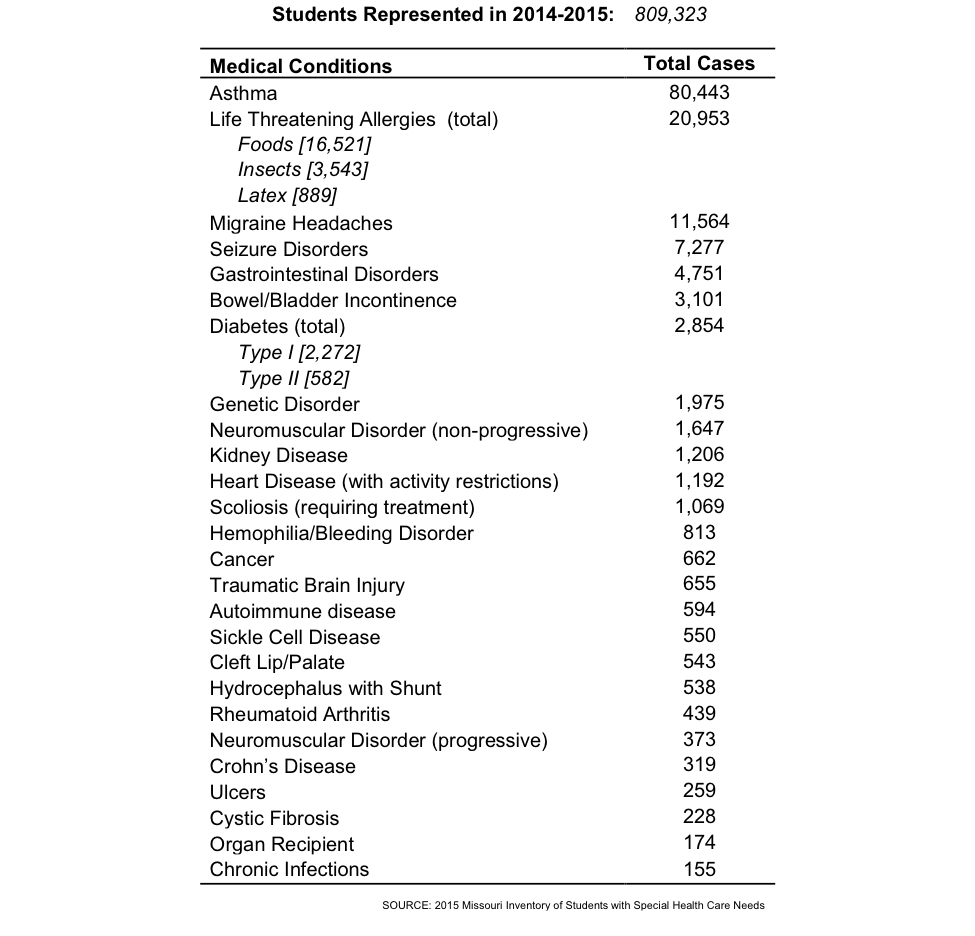

Medical Conditions

The most common condition reported among public school students was asthma (9.9%), followed by threatening allergies (2.6%), migraine headaches (1.4%), seizure disorders (.9%), and gastrointestinal disorders (.6%). Although the rest of the medical conditions reported were less common, it is important to consider the chronicity as well as the complexity of care needed for children with any of these conditions to be able to attend school.

An increasing number of students are entering schools each year with chronic health conditions that require management, intervention and coordination during the school day (see data trends on page 6). Some of these conditions are not only chronic requiring regular care and support, but some are also medically complex. School nurses must constantly balance the goals of keeping these children safe and well-managed, with the need to keep them in the learning environment. Children with medical conditions can experience barriers to learning and barriers to being present in the classroom because of issues related to their health, including side effects from medication, absences due to doctor visits, stress, pain, as well as ineffective coping skills.

School-based care coordination is the most effective strategy for keeping children with chronic conditions healthy and ready to learn. School nurses work with parents and caregivers to develop individualized health care plans and emergency action plans in case of a life-threatening event at school. School nurses also train school staff on these plans so that the students can be fully included in the school environment safely. The individualized health plan addresses medical orders and provisions appropriate to each student’s needs during the school day and other school-related activities. The emergency action plan is developed for the each student and instructs school staff on what to do in the event of an episode (“If you see this… Do this”).

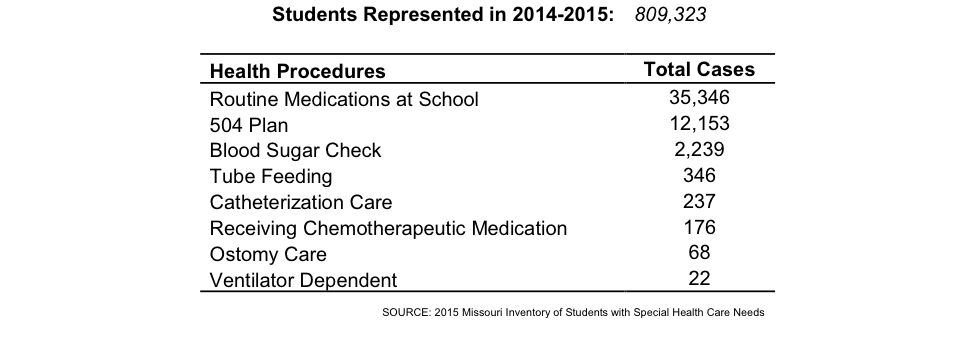

Health Procedures

The most commonly reported health procedures reported for public school students were receiving routine medications at school (4.4%), followed by 504 plans (1.5%), and blood sugar checks (.3%). Although the rest of the procedures reported were less common, their complexity should be noted.

In some cases, children requiring more complex care might need to see a school nurse multiple times during the school day. For example, when monitoring children with diabetes school nurses have to check blood sugar levels at different times during the day. In the case of ventilator dependent children, a nurse must be continuously available to watch for signs of respiratory distress. A school nurse may train and delegate these procedures to non-licensed personnel. However, the school nurse has ultimate responsibility for deciding which tasks can be delegated and to whom and for ensuring that the procedures are completed correctly. Some of these health procedures are challenging when performed in a physician’s office—having to perform them in the school-setting adds another layer of complexity as school nurses often juggle multiple responsibilities and demands.

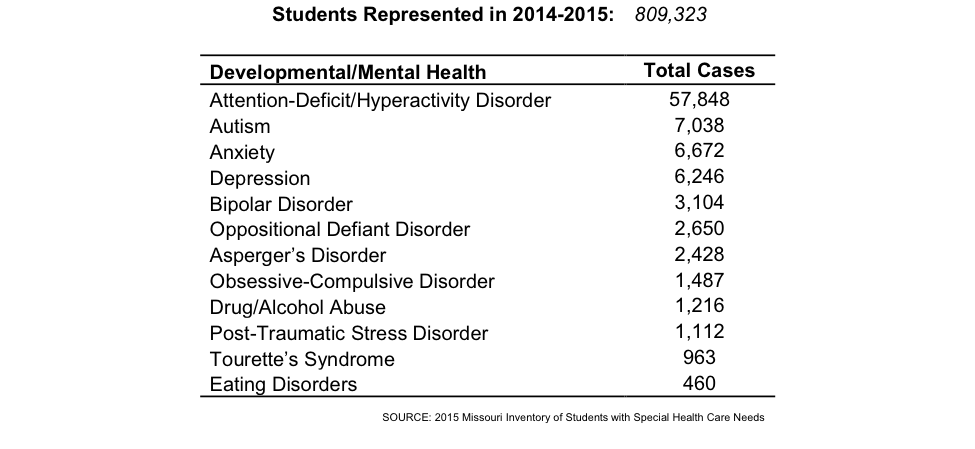

Development and Mental Health

The most common developmental and mental health condition reported for public school students was Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder [ADHD] (7.1%), followed by autism (.9%), anxiety (.8%), depression (.8%), and bipolar disorder (.4%).

School nurses, through the State School Nurse Consultant, their built network, and communities of practice have the evidence-based interventions and practices needed to manage chronic diseases—but these tools are not readily available for children’s mental health disorders.

School nurses are often ‘first responders’ on the front lines of children’s mental and behavioral health when children enter the school system and throughout their school years. School nurses are also frequently the first health professionals that refer children for further evaluation. Students often come to the health office with physical complaints, like headaches or stomachaches, masking the real concern of mental health.

School nurses work with counselors, social workers, and parents to identify the best care available for children with developmental and mental disorders. There is a need for school nurses to be better trained to address the needs of students with or at risk for emotional or behavioral difficulties that interfere with learning.

“Mental health concerns, particularly among older children, represent a challenge in our district. Finding someone in the community that can see or treat students with mental health concerns can

be challenging even in a metropolitan area. We are fortunate to have some programs in place to help with mental health, but it is still difficult to find help regarding long-term therapy or inpatient care.” —Missouri School Nurse

“When it comes to mental health, the school nurse is often the first person that the student will seek out. The school nurse is frequently the first point of contact. Students can often hide their mental issues with physical complaints, but school nurses can get to the root of the issue. School nurses can identify symptoms that might be indicative of mental health issues.” —Kathy Ellermeier, Director of Health Services for the Liberty School District.

Other Impairments

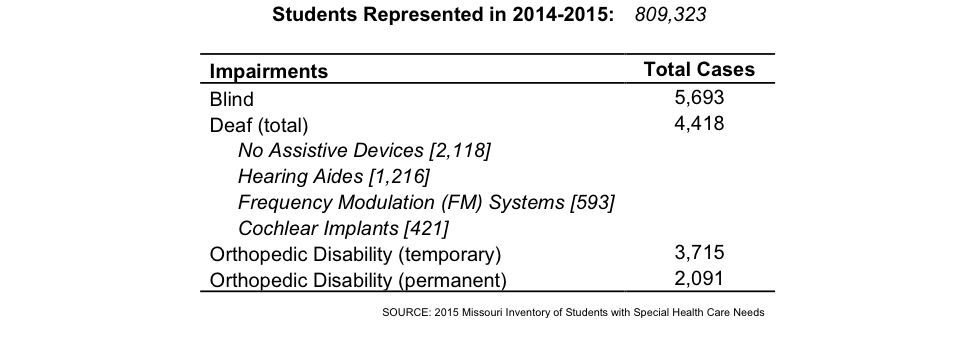

Among other impairments, the most common was blindness (.7%), followed by deafness (.5%), temporary orthopedic disability (.5%) and permanent orthopedic disability (.3%)

School nurses coordinate with school staff to create the best environment possible in which children with impairments can succeed. In order for children with impairments to be ready to learn they must first have to have the equipment and devices needed to be able to see, hear, or move. Unfortunately, many families cannot afford eye glasses, hearing aids, or mobility equipment for their children. As we will discuss in our next article, school nurses often connect families to financial resources first before they can address student health needs.

“Working with families with limited resources can be a challenge, particularly when children need glasses and hearing aids that they can’t afford. Children need to be able to see and hear in order to learn…as school nurses we do all we can to help families to connect with the resources they need.”—Dana Fifer, District School Nurse Manager at North Kansas City School District

“Children must complete vision and hearing screenings before enrolling in preschool. By following this system, we can identify children who might need glasses or hearing aids before they start school. By taking care of vision and hearing problems before they start school, we prevent children from falling behind in their studies.” —Patricia Wilson, Lead School Nurse for University City District

Trends for Selected Conditions

In this section, we compare the data collected during the past ten years for asthma, life-threatening allergies, seizure disorders, type I and II diabetes, and receiving routine medications at school. Although we do not discuss in this section trends in mental health, it should be noted that ADHD is one of the fastest growing conditions diagnosed among students. For illustration purposes, all rates are presented as the number of cases per 100,000 students.

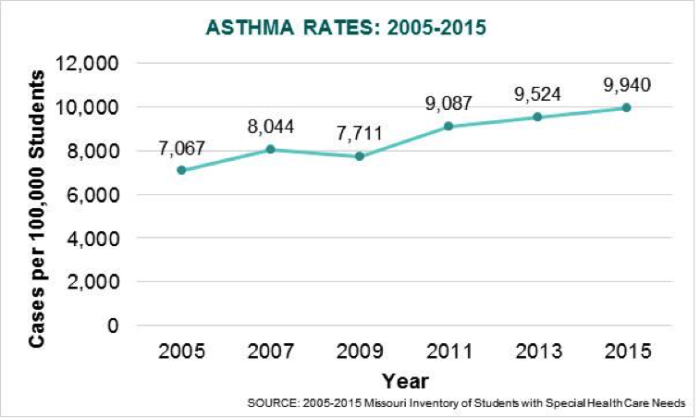

Asthma

The number of public school students diagnosed with asthma has increased by 41% in the last decade.

In order for students to be safe, engaged and fully participating at school, school nurses must train school staff on how to manage children with asthma. School personnel need to know how to recognize the onset of asthma, prevent exposure to the triggers and provide basic asthma care by remaining calm, stopping the student’s physical activity, removing any triggers, providing rescue medication and monitoring effectiveness of the response to the medication. Emergency asthma care is provided when the student needs prompt action due to the lack of improvement or worsening of symptoms after administration of rescue medication. Effective management of asthma can improve a student’s absentee rate, educational productivity, and well-being. School nurses require continuous professional development in order to be up to date with best practices for asthma.

School Nurse Stories about Children with Asthma

“A student was brought to my attention that had been according to her teachers apathetic, disinterested in school and practically sleeping through her school year. It was assumed she kept late nights and was depressed. After numerous attempts to get a history from her parents I was finally able to ascertain she was asthmatic. With some of the clarity I received from the DHSS asthma program I found out she literally lived in the ‘yellow zone’. She was poorly managed but because she did not present with symptoms of classic wheezing her asthma diagnosis was ignored even by her parents. After conferencing with her parents, doctor, staff and daily instructions from me, she was brought into the ‘green zone’. Her transformation was immediate—she literally came ALIVE. Now when a student is sent to me for ‘sleeping in class’ or some vague symptoms; I look for evidence of poor oxygenation and proceed from there.” —Missouri School Nurse

“A parent requested for two young boys to not be allowed to go out for recess or PE from November – March due to cold weather and asthma. It was realized that the parents didn’t have an understanding of asthma control and asthma medications. They had frequented the ER for asthma exacerbations which were very costly to the family. Financial issues were also a problem for the family to purchase the necessary medications. After discussions and education the two children were placed on asthma control medications, asthma education provided, follow up in the nurse’s office doing asthma assessment for breathing, helped with financial assistance for the asthma medications — the two boys were allowed to go outside for recess and activities. Their asthma has not been a challenging factor for them regarding physical activity since that time. They no longer required utilizing the ER for their asthma.” —Deb Cook, School Nurse, Kennett Public Schools

To learn more about Missouri’s efforts to reduce childhood asthma in the school setting, read our article about childhood asthma here.

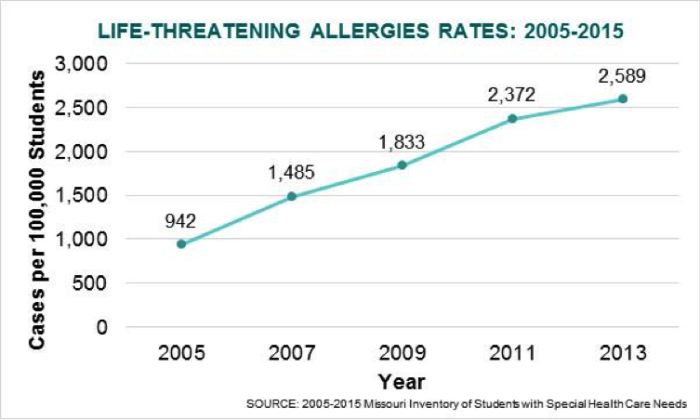

Life-Threatening Allergies

The number of public school students diagnosed with a life threatening allergy has increased by 238% in the last decade. The rates displayed below include food, insect, and latex allergies.

Addressing life-threatening allergies is one of the most important responsibilities of school nurses as their involvement can make the differences between life and death. Anaphylaxis is a serious type of allergic reaction that requires immediate treatment, including an injection of epinephrine or a trip to the emergency room. If not treated properly, anaphylaxis can be fatal. Fortunately, school nurses are well prepared to deal with life-threatening allergies in the school setting by coordinating, advocating, responding and educating the school community about allergy care.

School Nurse Story about a Child with Allergies

“A very concerned mom met with me about her child’s 9 food allergies. She reported that she was considering taking her child out of school and home schooling because she heard that our school does not have allergy free tables. I spent about 2 hours with mom listening to her fears, then spent time walking through the child’s IHP/504 plan and EAP. She went on to ask… ‘How can you guarantee that my child will not have an anaphylactic reaction at school?’ I answered honestly and replied: ‘I cannot guarantee but will make sure that our school staff continues to receive food allergy education.’ Just letting mom express her fears and process her concerns helped mom to allow her child to attend our school. —Linda Neumann, School Nurse, Webster Groves School District

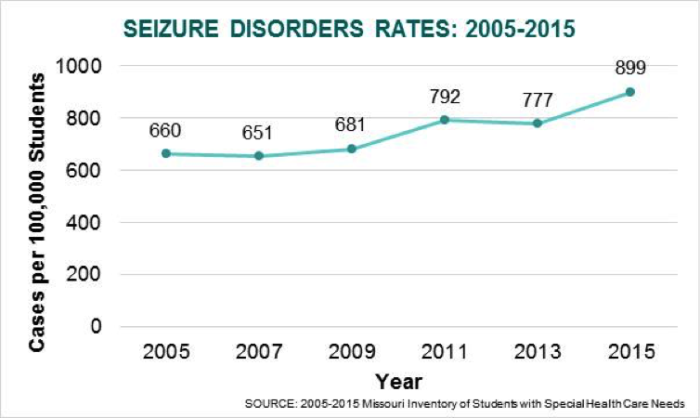

Seizure Disorders

The number of public school students diagnosed with seizures increased by 36% in the last decade.

The primary goal of the school nurse for a student with a seizure disorder is safety. The school nurse will assess the school and classroom environments to be sure they are free from triggers that may precipitate a seizure such as flashing lights or loud noises. With permission from caregivers and the student, the school nurse educates the teachers, school staff and bus drivers about first aid for seizures. School personnel need to know how to recognize seizures and how to respond to a seizure emergency. School nurses develop an emergency action plan to address seizures occurring in the classroom and other school settings, train school staff in seizure-related first aid, and provide assistance in the administration of daily and emergency medications for students with a seizure disorder.

School Nurse Story about Child with Seizures

“Seizures can be disruptive and sometimes cause injuries, but they can be controlled with treatment. When I was a middle school nurse I recognized that there was lots of stigma associated with epilepsy. My students with epilepsy did not participate fully in school. They dreaded being singled out, and were fearful of having a seizure when with their peers. There was a real potential for social isolation. I wanted my students and their parents to understand that epilepsy doesn’t have to stop you from enjoying your life and finding success in all you do. I invited the students to attend an information session ‘just for them’ with a speaker from the epilepsy foundation. First they learned that they were not the only one at school with epilepsy, there were several! It made for an immediate support group. The speaker shared other famous people with epilepsy, presidents, famous leaders, scientists, entertainers and athletes. We discussed getting a driver’s license, what to say on a job application, what to say to your friends. A well respected teacher sought me out. He too had epilepsy and had never shared with the school staff. He asked for permission to join the group. The students voted him in.” —Marge Cole, State School Nurse Consultant

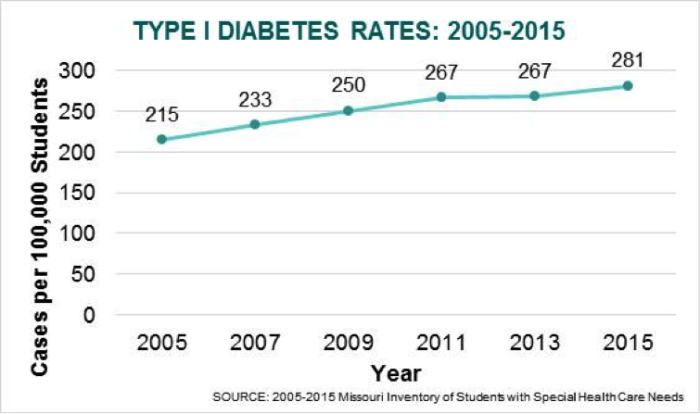

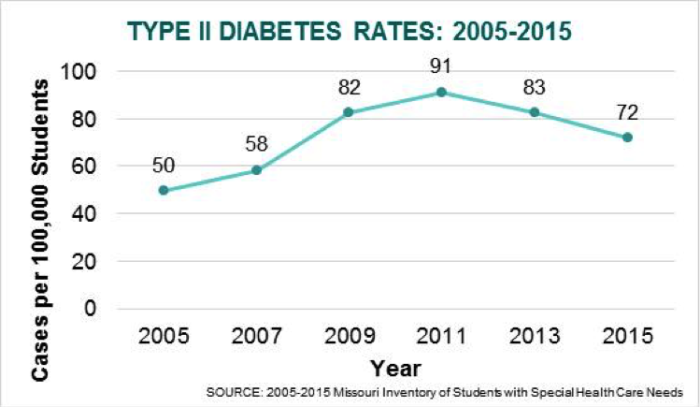

Diabetes Type I and Type II

Regardless of the specific type, the number of students diagnosed with diabetes has increased during the last decade. Specifically, type I diabetes (juvenile onset) increased by 30%, while type II diabetes (later onset) increased by 45%.

For children with diabetes, good diabetes management at school, where students spend the majority of their daytime hours, requires the school nurse to develop a care plan that takes into account whether the child uses medications, insulin injections, insulin pens or pumps, how often they need blood glucose checks, accommodating access to snacks and meal plans, water and bathroom breaks, while ensuring that the student with diabetes can participate fully and safely in the classroom and in extra-curricular activities. School nurses play the role of diabetes educator with students, teachers and staff, working with children on how to manage and live with diabetes.

Given the increase in the number of children with diabetes in Missouri, school nurses need to be part of the care team for these children, in coordination with the child’s other healthcare providers.

School Nurse Stories about Children with Diabetes

“As a nurse, I often think about my responsibilities, interventions and effectiveness as I go about my regular duties. Recently I was called to evaluate a student who was lethargic and had difficulty ambulating. There was no reported trauma. An assessment revealed no neurologic, respiratory or cardiac involvement. As I observed and monitored the student, I thought about a review of the other body systems and what might be going on. When the mother came to pick her child up, I asked if there was a family history of diabetes. She said no. I advised her to take her child to a health care provider for further evaluation. She agreed and took her child to the ER. The next day she called and said her child had been diagnosed with diabetes and had been admitted to the hospital. The student has since returned to school and is adjusting to the change in his lifestyle. I am grateful that I was able to utilize my knowledge, skills and instincts to assist this family in seeking a timely medical intervention”. —Missouri School Nurse

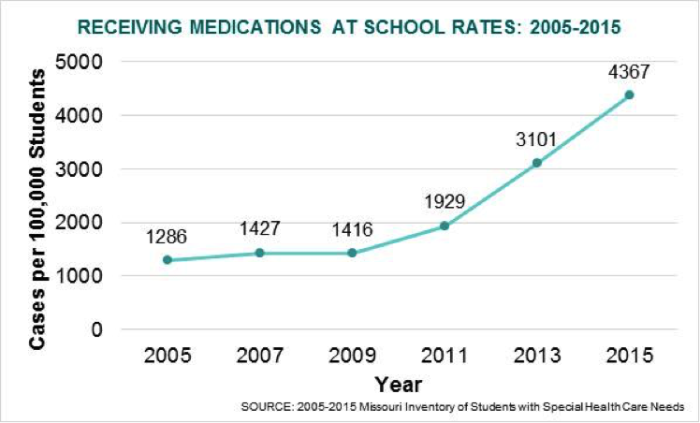

Receiving Routine Medications at School

Considering the increasing trends in chronic conditions, it is not surprising that the number of students receiving routine medications at school has also increased. Specifically, the number of public school students receiving routine medications at school has increased by 240% in the last decade.

Students can receive different types of medications at school. Children with chronic conditions may have a regimen of daily medications that school nurses are responsible for managing. In addition, school nurses also responsible for administering emergency medications, such as injections of epinephrine to a student experiencing a severe allergic reactions or a sedative for a prolonged seizure. With prior parent permission, school nurses can also give urgent medications to students, including painkillers and antihistamines to help treat unexpected symptoms. Medication administration at school is a serious responsibility that requires a high level of attention and time to avoid potential errors. As the number of children receiving medications at school continues to increase, more school nurses and trained school staff will be needed to help manage this important task.

Parent Thank You Note to School Nurses for Detecting a Medication Error

“Last week our family experienced a very difficult health event with our daughter. She was diagnosed at Children’s Mercy Hospital with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. It has been a very difficult week for our family. We are very grateful for several things with regard to our daughter’s care and transition during this stressful time. The first being the nurses in the Health Services area. It is no exaggeration when I say that due to their diligence in medication management they have prevented grave injury to our daughter. When checking in medications through their office, they notice an incorrect dosage by a local pharmacy of a very potent anti-seizure medication. If this error would have gone unnoticed by these professionals, the pharmacist said it could have had dire consequences to our daughter. I am very grateful that someone cares so much and takes their job so seriously they may have saved my daughter’s life.” —Parent, Liberty Public Schools

As presented in this article, the data collected by school nurses in public schools and aggregated by the State School Nurse Consultant presents a unique and eye opening view of child health in Missouri. It should be noted that this data is limited to children attending public school; thus, the reported cases and rates are likely underestimates of the state rates. We are grateful to all the school nurses who have diligently collected and submitted their data and invite others to participate in this effort. While Missouri’s data collection effort is nationally recognized, it is also notable for what it does not collect—particularly important to child health is oral health and health insurance coverage status. In our final article in this series we will have a call to action that will include additions to the data collection.

Inspiring Stories

In this section we present three stories sent to us by school nurses from Sedalia, Carl Junction, and Webster Groves coordinating with local hospitals to provide better care for students. In the first two examples, teamwork, effective communication, follow up, care coordination including the school nurse as part of the care team, have resulted in a much stronger health care network in these communities. In the third example, a school nurse and a local hospital worked together to supply necessary life saving devices for the school district.

Same Day Kids—Sedalia School District

In partnership with Katy Trail Community Health, school nurses in the Sedalia School District created

Same Day Kids—an email program that facilitates communication between the school nurses and the local

clinic. When a student needs to be seen by a health professional, the school nurse sends an email through

Same Day Kids, including the reason why the child needs to be seen and potential insurance concerns.

The email is received by personnel in the clinic, including the medical and dental clinic manager, the care coordination team, medical records, and appointment desk. The school nurse then receives a response from the clinic including the appointment time and person who will see the child. By streamlining the communication process between the school nurses and the clinic staff, the child is able to receive the care needed the same day, thus reducing the time spent outside of the classroom. In addition, school nurses receive information back from the clinic, including treatment details and follow ups, thus facilitating appropriate care coordination for the child.

School-Based Health Program—Carl Junction School District

After the catastrophic tornado that struck Joplin in 2011, school nurses in the Carl Junction School District noticed a higher influx of student visits to the nurse office. The school nurses took it upon themselves to find the reason for the sudden increase in visits. After conducting community assessments, the school nurses determined that the community did not have the resources necessary to meet the health needs of their population. School nurses met with school administrators and local community hospital leaders to brainstorm ideas on how to better serve the community. As result, Carl Junction Schools, in partnership with Freeman Health System, developed a school-based health program to address the health needs of students and staff (read more about the program, here). By taking a leadership role and having the support of the school administration, school nurses from Carl Junction were able to make a difference in their community.

Partnering with a Local Hospital to Provide AEDs—Webster Grooves School District

An automated external defibrillator (AED) is a device that is used to treat sudden cardiac arrest, a condition in which the heart suddenly stops beating. Having an AED available at school is vital as sudden cardiac arrest can cause death if is not treated within minutes. A school nurse in the Webster Grooves School District recognized the importance of having reliable AEDs and decided to search for way to replace the old devices. Given that the school district was experiencing financial difficulties, the school nurse took matter on her own hands:

“Our ‘old’ expired AED’s needed to be replaced and our cash strapped school district, which had just had a tax and bond issue voted down, had no money! I reached out to a local hospital and to my surprise they had a foundation that could help (they had never been asked by a school for help). I wrote a grant request and we received $15,000 for new AED’s. Prior to writing the grant, I also reached out to one of the school nurse supply companies and asked them for a discounted price, which that gave us”. — Linda Neumann, School Nurse at Webster Groves School District

Thanks to the initiative of this school nurse, the Webster Groves School District is now prepared for medical emergencies requiring the use of AEDs.

Summary

As you can see school nurses play an indisputable role ensuring that children have access to health care when they are in school. Using evidence-based practices, their strong network of peers and the State School Nurse Consultant, they effectively address chronic disease, are first responders to acute illness and injury, and provide critical prevention and wellness initiatives—all aimed at keeping children in school, learning and thriving. Although the focus of this article is to educate the public about the complex and chronic diseases and conditions that school nurses see each day, it should be noted that school nurses are also responsible for providing or coordinating care for children without chronic conditions including: immunization assessments, vision and hearing screenings, first aid, and emergency care—to name a few.

Coming Up Next…

Children cannot be whole, happy and ready to learn if the ‘non-medical’ problems remain. For children living with chronic diseases like asthma, life-threatening allergies, seizure disorders, and diabetes, the social and emotional burdens are very real but often hidden. And many children, regardless of health status, come to school hungry, inadequately dressed, with anxiety and depression, carrying the effects of trauma. The next article in our series on school nurses in Missouri will focus on the challenges school nurses face that requires them to go beyond their traditional medical training. We will also highlight the critical role of the State School Nurse Consultant in supporting and sustaining school nurses.

Suggested Citation

Hines, L., Cole, M., & Martinez, M. M. (2016, January). School Nurses and School-based Healthcare: The Data and the Stories. The Family and Community Trust (FACT)—Missouri KIDS COUNT. Available at: http://mokidscount.org/stories/school-nurses-and-school-based-healthcare-the-data-and-the-stories/

Acknowledgments: We would thank everyone who contributed to the article, whether through interviews or stories. We are grateful to the University of Missouri Center for Family Policy and Research for their expertise.

Funding for Missouri KIDS COUNT is generously provided by the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

January 11, 2016